Addressing the Opioid Crisis: Medication-Assisted Treatment at Health Care for the Homeless Programs

Introduction

As providers of comprehensive health care services in medically underserved areas, community health centers play an important role in addressing the opioid epidemic.1 Health Care for the Homeless (HCH) programs are community health centers that serve people experiencing homelessness, who are often disproportionately impacted by SUD, including OUD. Funded through the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), HCH programs receive special populations funding that allows for more intensive services to meet the specific needs of very vulnerable and medically complex patients.2 Of note, HCH grantees are required to provide or arrange for SUD treatment services, and they typically provide more case management, outreach, and other support services than non-HCH health centers.3 In some cases, HCH programs are part of larger health centers, while in other cases they are stand-alone organizations. In 2017, there were 1,373 health centers that served nearly 1.4 million patients experiencing homelessness; 74% (just over 1 million) of these patients were served by 299 HCH programs.4

The standard of care for OUD is medication-assisted treatment (MAT), which combines one of three medications (methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone) with behavioral therapies, and is associated with better outcomes than behavioral therapies alone.5 In order to prescribe buprenorphine to treat OUD, an eligible provider must obtain a waiver from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).6 Compared to other health centers, HCH grantees are well-positioned to offer MAT services because of a more intensive care model that has long-emphasized integrated behavioral health and primary care coupled with a low-barrier, harm-reduction approach to patient engagement.

This brief describes the provision of buprenorphine (also known by trade names Suboxone®, Zubsolv®, and Subutex®, among others) at HCH programs relative to other health centers, the growth of these services between 2016 and 2017, and the availability of buprenorphine at HCH programs in states hard-hit by the opioid epidemic. It also highlights successful strategies that HCH programs have used to implement buprenorphine-based MAT programs. Findings are based on an analysis of annual data from the Uniform Data System (UDS) on health center patients and services,7 and on interviews with providers and administrators from 12 HCH programs conducted by the National Health Care for the Homeless Council and the Kaiser Family Foundation. These data and strategies can help inform where MAT might be further expanded, and guide efforts to implement MAT programs at other health center programs and more broadly. In this paper, the term “MAT” refers to buprenorphine-based MAT specifically.

Providing Buprenorphine at HCH Programs

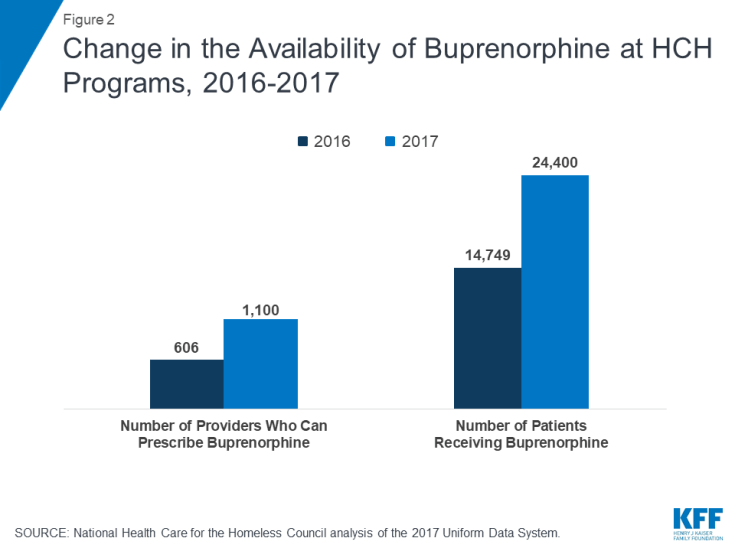

HCH programs provide a greater share of buprenorphine treatment compared to their overall patient numbers. In 2017, HCH programs nationally reported having 1,100 providers with a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine, and delivered buprenorphine to 24,400 patients (Figure 1). While HCH programs account for only 4% of all patients served at health centers nationally, over one-third (37%) of buprenorphine-waivered providers and 38% of all patients receiving buprenorphine were affiliated with HCH programs.

Figure 1: Overall Utilization and Utilization of Buprenorphine Services at HCH and non-HCH Health Centers, 2017

Greater patient need as well as a more intensive treatment model that includes SUD services may help to explain why HCH programs are providing a greater share of buprenorphine-based MAT services. These programs serve a patient population that disproportionately struggles with SUDs, to include OUD. Because of the unique needs of their patients, HCH programs are required to offer SUD treatment services, though not buprenorphine-based MAT specifically, as part of their special populations grant. As a result, many of these clinical settings have developed treatment models that integrate primary care and behavioral health services, provide intensive supports, and emphasize lower-barrier approaches to accessing care. This care model strongly positions these programs to provide buprenorphine services specifically, as well as more comprehensive SUD treatment generally.

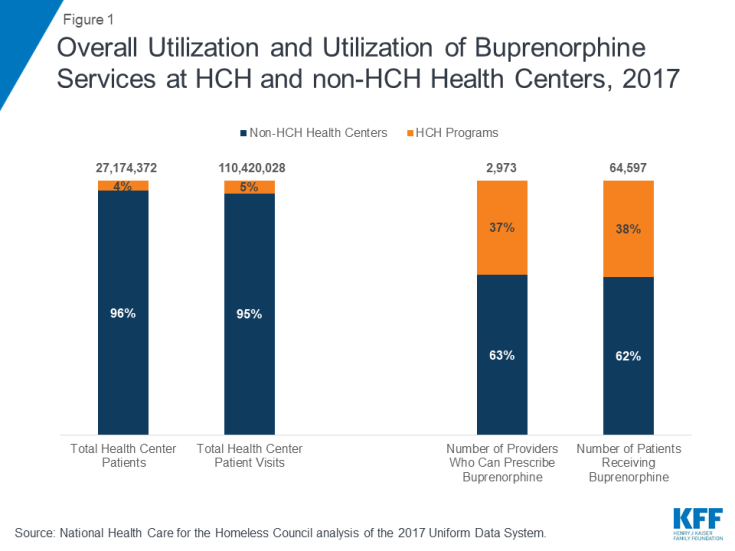

As with health centers nationally, both the number of buprenorphine-waivered providers as well as the number of patients getting treatment at HCH programs increased significantly between 2016 and 2017. The number of providers increased 82% across HCH programs, from 606 to 1,100, while the number of patients increased 65%, from 14,749 to 24,400 (Figure 2). These increases demonstrate how HCH programs have used resources to respond to the growing demand for treatment as the opioid epidemic has escalated.

While the national data paint a broad picture, the provision of buprenorphine by HCH programs varied widely across states. Not all states (or all HCH programs within a state) are facing the same challenges from the opioid epidemic, and not all HCH programs are expected to be delivering the same level of OUD services. Consequently, while HCH programs in 19 states served fewer than 100 patients in 2017, HCH programs in other states had many providers who could prescribe buprenorphine, were prescribing buprenorphine to large numbers of patients, and had significant year-over-year increases in both MAT providers and patients receiving buprenorphine (Table 1). Between 2016 and 2017, HCH programs in 24 states saw at least a doubling of the number of staff able to prescribe buprenorphine and in 20 states provided buprenorphine-based MAT to at least twice as many patients. Policy changes that now allow nurse practitioners and physician assistants to prescribe buprenorphine may account for some of the increase, as well as numerous funding opportunities to train additional providers and increase capacity for care. HCH programs in several states saw decreases in the number of waivered providers or patients served; however, this decline may result from staff turnover rather than a decreased commitment to providing MAT, or it may reflect a greater availability of treatment options for patients in their communities.

Importantly, in states hardest hit by the opioid epidemic, particularly in New England, the Mid-Atlantic, and parts of the Midwest,8 many HCH programs have active buprenorphine programs. In 15 of the 23 states with the highest opioid-related overdose death rate, at least half of HCH programs are providing buprenorphine, and in nine states, at least two-thirds of all of the HCH programs are providing MAT (Table 2). However, some states continue to have low buprenorphine-based MAT provision among HCH programs, particularly in Kentucky and Tennessee, even though there may be a significant need for these services in their communities. (The data for this report do not indicate why MAT service levels are low in these areas.) Providing buprenorphine-based MAT remains only a small part of the services most HCH programs deliver, but some HCH programs have made a greater commitment to providing MAT than others. HCH programs in three states (CT, RI, and VT) are providing buprenorphine to more than 15% of their patients, and MAT programs in an additional six states (MA, MD, NC, NH, NM, and WV) are serving 5% or more of their total patients. Because health centers tailor their services based on local need, these data highlight where HCH programs are currently providing extensive buprenorphine-based MAT in alignment with community need and where further expansions may be considered. Conversely, in states where OUD may not be the most significant issue, HCH programs may not be prioritizing the development of active buprenorphine programs.

| Table 1: Number of Buprenorphine Providers and Patients Served at HCH Programs, 2016 -2017 | |||||||

| State | Number of HCH Programs, 2017 | Number of Buprenorphine Providers, 2016 |

Number of Buprenorphine Providers, 2017 |

Change in Number of Buprenorphine Providers, 2016-2017 |

Number of Patients Receiving Buprenorphine, 2016 | Number of Patients Receiving Buprenorphine, 2017 | Change in Number of Patients Receiving Buprenorphine, 2016-2017 |

| Alabama | 4 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 67 | 67 |

| Alaska | 2 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 11 | 192 | 181 |

| Arizona | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Arkansas | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| California | 45 | 156 | 316 | 160 | 3033 | 4373 | 1340 |

| Colorado | 5 | 3 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 107 | 97 |

| Connecticut | 8 | 22 | 38 | 16 | 773 | 1860 | 1087 |

| Delaware | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 16 | 16 |

| District of Columbia | 1 | 0 | 17 | 17 | 0 | 98 | 98 |

| Florida | 16 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 100 | 371 | 271 |

| Georgia | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 30 | 34 | 4 |

| Hawaii | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 23 | 23 |

| Idaho | 2 | 5 | 11 | 6 | 347 | 236 | -111 |

| Illinois | 8 | 9 | 24 | 15 | 343 | 694 | 351 |

| Indiana | 6 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 120 | 467 | 347 |

| Iowa | 4 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 60 | 145 | 85 |

| Kansas | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Kentucky | 7 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 84 | 79 |

| Louisiana | 6 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 91 | 80 | -11 |

| Maine | 2 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 15 | 121 | 106 |

| Maryland | 2 | 10 | 13 | 3 | 541 | 493 | -48 |

| Massachusetts | 7 | 65 | 95 | 30 | 1860 | 2279 | 419 |

| Michigan | 14 | 11 | 24 | 13 | 306 | 731 | 425 |

| Minnesota | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 53 | 150 | 97 |

| Mississippi | 2 | 2 | 0 | -2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Missouri | 3 | 4 | 9 | 5 | 15 | 134 | 119 |

| Montana | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 32 | 32 |

| Nebraska | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nevada | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 136 | 151 | 15 |

| New Hampshire | 3 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 243 | 373 | 130 |

| New Jersey | 7 | 9 | 13 | 4 | 962 | 733 | -229 |

| New Mexico | 6 | 19 | 52 | 33 | 1278 | 1504 | 226 |

| New York | 21 | 48 | 104 | 56 | 1576 | 3320 | 1744 |

| North Carolina | 10 | 9 | 18 | 9 | 105 | 582 | 477 |

| North Dakota | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ohio | 8 | 34 | 37 | 3 | 541 | 866 | 325 |

| Oklahoma | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 11 | 160 | 149 |

| Oregon | 12 | 45 | 66 | 21 | 623 | 1076 | 453 |

| Pennsylvania | 6 | 20 | 10 | -10 | 1 | 318 | 317 |

| Puerto Rico | 5 | 12 | 16 | 4 | 116 | 136 | 20 |

| Rhode Island | 2 | 18 | 28 | 10 | 443 | 422 | -21 |

| South Carolina | 4 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 28 | 28 |

| South Dakota | 2 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 21 | 45 | 24 |

| Tennessee | 7 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 78 | 335 | 257 |

| Texas | 12 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 31 | 31 |

| Utah | 3 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 86 | 261 | 175 |

| Vermont | 1 | 13 | 16 | 3 | 273 | 370 | 97 |

| Virginia | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 50 | 50 |

| Washington | 7 | 29 | 58 | 29 | 148 | 367 | 219 |

| West Virginia | 1 | 4 | 12 | 8 | 383 | 473 | 90 |

| Wisconsin | 3 | 4 | 1 | -3 | 12 | 5 | -7 |

| Wyoming | 1 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 473 | 0 |

| Total | 299 | 606 | 1,100 | 491 | 14,749 | 24,400 | 9,584 |

| SOURCE: National Health Care for the Homeless Council and Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the 2016 and 2017 Uniform Data System (UDS). | |||||||

| Table 2: Share of HCH Programs Reporting Buprenorphine Patients and HCH Patients Receiving Buprenorphine as a Share of All HCH Patients in Hard-Hit States | ||||

| State | Opioid-related Overdose Death Rate* | Number of HCH Programs | Share of all HCH Programs Reporting Buprenorphine Patients | Patients Receiving Buprenorphine as a Share of Total HCH Patients |

| West Virginia | 43.4 | 1 | 100% | 6% |

| New Hampshire | 35.8 | 3 | 67% | 6% |

| Ohio | 32.9 | 8 | 63% | 4% |

| Maryland | 30.0 | 2 | 50% | 5% |

| District of Columbia | 30.0 | 1 | 100% | 1% |

| Massachusetts | 29.7 | 7 | 71% | 9% |

| Rhode Island | 26.7 | 2 | 50% | 27% |

| Maine | 25.2 | 2 | 100% | 3% |

| Connecticut | 24.5 | 8 | 38% | 17% |

| Kentucky | 23.6 | 7 | 14% | 1% |

| Michigan | 18.5 | 14 | 36% | 2% |

| Pennsylvania | 18.5 | 6 | 50% | 1% |

| Vermont | 18.4 | 1 | 100% | 22% |

| Tennessee | 18.1 | 7 | 29% | 2% |

| New Mexico | 17.5 | 6 | 83% | 9% |

| Delaware | 16.9 | 2 | 50% | 2% |

| Utah | 16.4 | 3 | 67% | 4% |

| New Jersey | 16.0 | 7 | 43% | 4% |

| Missouri | 15.9 | 3 | 67% | 1% |

| Wisconsin | 15.8 | 3 | 33% | <1 |

| North Carolina | 15.4 | 10 | 40% | 5% |

| Illinois | 15.3 | 8 | 50% | 4% |

| New York | 15.1 | 21 | 62% | 4% |

| Source: National Health Care for the Homeless Council and Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the 2017 Uniform Data System (UDS) and Kaiser Family Foundation’s State Health Facts | ||||

Strategies for Successfully Providing Buprenorphine-based MAT at HCH Programs

HCH programs use a number of wide-ranging strategies to overcome common challenges to providing buprenorphine-based MAT services to their patients. These strategies address the need to build support among leadership and clinical staff, provide training and assistance to clinical and non-clinical staff, modify existing systems and adopt flexible programs to enhance capacity and access, and maximize community partnerships resources. The following discussion highlights themes from interviews with CEOs, program administrators, physicians, and behavioral health staff at 12 HCH programs.

Organizational SUPPORT and buy In

Identifying champions within HCH programs who will advocate for establishing MAT programs is essential to building the necessary support from leadership and clinical staff. Initiating MAT services can be difficult when board members, CEOs or other executive leaders, and/or providers do not feel that SUD is an issue that health centers should be prioritizing. This challenge can be particularly acute when leadership or clinical staff refuses to recognize MAT as an evidence-based practice and a standard of care, preferring instead a more traditional abstinence-focused model. To overcome these attitudes and build support within their organizations, respondents reported identifying “champions” within their agencies who were passionate about addressing OUD and were willing to advocate for the benefits of establishing a MAT program. These champions worked to help leadership recognize MAT as a valuable service consistent with the HCH program’s mission. Recruiting champions who can speak to the concerns from both primary care and behavioral health staff can facilitate coordination across the two disciplines.

“The main barrier to setting up programs is having buy-in from organizational leadership and Board members, even if your providers are on board. Not everyone feels addiction is an issue that FQHCs should be solving—we are so busy providing other services and this is just one more thing we’re supposed to do.” (Physician, Virginia)

“Get someone to be a champion for you, do the education, spend time with others doing MAT, and start an internal mentoring program.” (Physician, New York)

“You have to have a champion. There’s a lot of projects going on and if no one is truly passionate about it, it dies off.” (Physician, New Jersey)

Consulting with more experienced HCH programs to share lessons learned and address concerns can reduce barriers to establishing a MAT program. Several programs were able to engage in peer-to-peer technical assistance efforts, to include visiting clinical sites with established MAT programs to talk directly with providers, patients, and leadership. These visits provided insights into how programs were initiated, how they expanded over time, and how they currently operate. They were also able to share lessons learned and strategize approaches to overcome specific challenges. Respondents who had participated in these visits noted that staff returned from the visits energized and committed to starting a program.

“We had staff members go to another FQHC and walk through the details of their program and everyone came back feeling much more confident.” (Program Director, Maine)

Acknowledging and addressing concerns about medication diversion may be necessary to gaining provider support for a MAT program. A number of clinicians expressed concern about repercussions to their medical license if patients divert the medications they are prescribed. At the same time, providers also acknowledged that many patients have successfully self-medicated with buprenorphine purchased on the street, and that accessing traditional treatment programs is often difficult for very vulnerable people struggling with stability. They conceded the use of diverted medications is a harm reduction approach that reduces overdose risk and facilitates a treatment pathway when patients are ready to make a stronger commitment to a more formal addiction program. The conflict between concern over diversion and interest in harm reduction and overdose prevention creates a dynamic that some providers said they struggle to address. Several providers noted the importance of addressing diversion directly with their patients when they suspect or become aware of it happening. Although potentially difficult and tense, these conversations are necessary to reaffirm patients’ commitment to treatment and to ensure the integrity of the MAT program.

“I know people sell their buprenorphine and to me as a provider, it puts my medical license on the line if we don’t monitor use really tight.” (Physician, Utah)

“Diversion isn’t the biggest problem—overdosing and dying is the biggest problem. People don’t use bup[renorphine] to get high.” (Program Director, Maine)

“I see patients all the time who tried buprenorphine on the street and wanted their own place in a program because it worked well for them.” (Physician, DC)

“It’s actually pretty rare that my patient isn’t taking the medication I prescribe for addiction. When that happens, you have an honest conversation together.” (Physician, Virginia)

Staff Training and Support

Providing training and support to primary care providers who lack expertise in treating OUD can increase their willingness to provide MAT services. Some primary care providers expressed a genuine interest in providing MAT, but acknowledged that they did not have the clinical training, skills, or core competencies to confidently screen and treat patients with OUD. As primary care providers, they also recognized that they were ill-equipped to confidently navigate relapse episodes, and some had difficulty finding harm reduction strategies that would continue engaging vulnerable patients in care. In response, respondents from successful MAT programs reported conducting regular trainings on addiction, harm reduction, motivational interviewing, and other evidence-based approaches to build effective skills for engaging patients in treatment. Some also noted having success in pairing new providers with more experienced ones to allow for mentoring. Another approach for programs was to start small with only a few patients, and expand patient caseloads as provider skills and comfort levels increased.

“Start small—you just want a drink of water, not to be blown away by a fire hose.” (CEO, North Carolina)

“Prescribing buprenorphine has brought the joy back into my work and you don’t get that a lot in primary care because everyone’s burned out. You get to see palpable patient success—they aren’t overdosing, they get a job, they reunite with family and friends—it’s incredibly gratifying.” (Physician, New Jersey)

Engaging staff throughout the organization and fostering coordination between primary care and behavioral health staff helps broaden staff support for the program and can improve quality of care for patients. Respondents reported collaborating with a broad range of team members to develop standards of care and program policies that would meet the needs of a vulnerable patient population. They worked to include community health workers, peer specialists, and outreach workers in training opportunities and used these positions to help locate and re‑engage patients who had become disconnected from care. In addition, some program staff reported holding regular case conferences with team members from primary care and behavioral health to address both client-specific issues and program-wide concerns. In addition to addressing specific cases, these meetings served to build stronger working relationships across the two disciplines. Some respondents also reported their programs allow all staff members, including nurses, case managers, and social workers, to refer patients to their MAT programs in order to maximize access to MAT services and increase staff investment in the success of the program.

“Behavioral health counselors and primary care providers are two disciplines that don’t always work well together. We’ve had weekly meetings with everyone involved, get buy-in on patient cases, and agree on how to best support patients with addiction. Establishing a respectful relationship across disciplines takes time and leadership and a commitment to working together.” (Physician, Virginia)

“Now we will be using community health workers and street outreach teams to lower barriers to our rural program.” (Program administrator, Maine)

“A turning point came when NPs (nurse practitioners) and PAs (physician assistants) could prescribe—they were more open to doing this and our program expanded from there.” (Physician, DC)

Dedicating administrative staff for MAT programs can alleviate burdens on clinicians and allow more time for patient care. In addition to training requirements for provider prescribing, federal law also requires providers to keep patient logs and track other administrative data, which can be time-consuming. In response, some HCH programs identified dedicated staff to coordinate the MAT programs, reserve patient visits in provider schedules, and keep track of MAT documentation requirements. Another challenge voiced by many respondents is the requirement from many Medicaid managed care organizations and other insurers to obtain prior authorization before initiating MAT. Respondents noted this process is staff-intensive and creates delays of several days or more before treatment can be started, reducing the window of opportunity to engage a patient in treatment. Having a staff person dedicated to completing prior authorization requests can facilitate obtaining the authorizations in as timely a manner as possible. Respondents also reported working with insurance plans (or the state) to waive prior authorization requirements for those diagnosed with OUD.

“Most of our insurance plans still require prior authorizations. We have two full-time dedicated staff who only do prior authorizations and it’s incredibly time intensive. Most places don’t have the staff to do this.” (Physician, DC)

Setting expectations for participation in MAT programs by current and new staff and recruiting already-waivered providers can help advance acceptance of MAT. Several respondents mentioned that they had encountered other providers who simply did not prefer to work with patients who had SUD, desiring a more traditional primary care scope of practice. While this was often attributed to long-time providers who believed they would be overwhelmed by unmanageable patients, this viewpoint could inhibit MAT services. In turn, clinical leaders said that they now look to hire new providers who already have their waiver, and they set the expectation that MAT participation is part of the model of care provided.

“Coming in for a primary care visit shouldn’t ignore your addiction issues. Providing patient-centered care means addressing all of it—even the messy stuff.” (Physician, New Mexico)

“We’ve had docs say “I just want to do medical and be a good ole family doc and not get into all that”—I don’t hire those people anymore.” (Physician, New Jersey)

program Flexibility

Modifying internal systems to meet the unique demands of MAT programs can increase provider capacity and facilitate patient adherence with treatment. Clinicians at some HCH programs noted that it was difficult to find room in their busy schedules to accommodate frequent visits often needed by MAT patients to refill or adjust their prescription or to “check-in” on their current status with treatment. Many said that their appointment calendar is booked out weeks in advance, leaving little opportunity to add new patients who likely needed more time and attention than they had available. In response, successful HCH programs adjusted schedules to block out dedicated time for MAT patients and made other changes to eliminate barriers to treatment. For example, some HCH programs reserved same-day, walk-in appointments for MAT patients, scheduled evening services to accommodate those who could not access treatment during the day, and created a central call number where patients could get more information. As mentioned above, other staff roles have been used to help support patients, which allows providers more time to focus on clinical care.

“The demand on capacity is huge—I need more staffing for intake, assessment, prescribing and therapy, and I just don’t have it.” (Physician, Utah)

“Starting in January, all our MAT providers will have a block of same day appointments for easy access and follow-up.” (Physician, DC)

Adopting a more flexible approach to the therapy component of MAT services based on patient needs can improve access to treatment. Patients struggling with homelessness and addiction (as well as other issues) may not be able to navigate more structured programs, complete assessments, wait for insurance approvals, or have the time or transportation to attend frequent therapy sessions or visits for prescription refills. As a result of complex patient needs (to include unstable housing), they say engagement in treatment can vary widely with some individuals starting and stopping treatment suddenly, which can be difficult for program continuity and improving patient health outcomes. Some respondents were concerned that patients needed more therapy support in their recovery than they were able to provide, while others stressed the importance of lowering barriers to care by starting treatment immediately rather than requiring a program orientation, extensive assessments, or rigid adherence to an intensive therapy component. These divergent viewpoints illustrate that providers continue to evaluate how best to deliver care to a high-need population requiring intense services.

“We have a highly structured MAT program that works well for our patients who have resources and are more stable, but we found this didn’t work well for more vulnerable patients. Now, we’re developing a low-barrier, rapid-access program to better serve our higher-needs clients.” (Program administrator, Maine)

“I’ll bet only about ¼ of our MAT patients participate in groups regularly, but our experience is that this isn’t possible or desirable—not everyone needs the same approaches and that’s okay.” (Physician, DC)

“We had many conversations about being patient-first, meeting people where they are, and decreasing barriers to treatment. We stopped doing an orientation, started people on treatment on day one, are doing more patient-centered care, and are now partnering with other organizations.” (Physician, New Mexico)

Community partnerships and RESOURCES

Working with community providers and organizations can facilitate access to and reduce barriers to treatment for patients. These partnerships involved local hospitals and other medical providers, as well as housing and social service organizations. To initiate treatment, some HCH programs developed agreements with local hospitals or emergency departments providing the first dose of buprenorphine when patients presented for treatment and then referring them to an HCH program for ongoing care, while others formed partnerships with other community providers, such as the community mental health center, to maximize treatment resources for patients. Some respondents noted that homeless services providers (shelters, housing programs, etc.) may prohibit clients who take medications for OUD, which forces patients to choose between treatment and shelter. These restrictions, in turn, reduce the effectiveness of treatment and the willingness of some providers to invest in developing MAT programs that they feel may have limited impact. In an effort to reduce this barrier, some HCH programs reported working to create a greater understanding of MAT with local homeless service providers to ensure that patients could access shelter or housing while they were in treatment.

“Our partnership with two community mental health centers has worked well to help initiate buprenorphine treatment in a behavioral health setting and refer patients back to our clinic for primary care and ongoing OUD management.” (Program administrator, Maine)

“There’s a ton of rehab places in the city but they are not very flexible—they don’t even allow any medications that help them [patients] stay sober.” (Physician, Texas)

“When our clients live in an abandoned building, buprenorphine alone is not going to solve all their problems—they are afraid for their safety, they are hungry and cold. We need more housing so the treatment can work better.” (Addiction counselor, Maryland)

Maximizing available funding and training resources can help initiate and expand MAT programs. Numerous grant opportunities have been made available from both the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) to train providers, increase clinical skills, and expand capacity for treatment. Respondents also pointed to grants and other training opportunities from state/local health departments, professional organizations, Project ECHO [an online, peer-to-peer training model], and other sources. With competing priorities and limited funds, particularly for HCH programs in states that have not expanded Medicaid, taking advantage of these federal and other resources can be critical to starting a program and refining it to match patient needs and provider capacity.

“Project ECHO was helpful in overcoming concerns, fears, and worries. We did a buprenorphine ECHO to present cases, get answers, and hear that we weren’t alone.” (Physician, New Jersey)

“DC gave us a grant to build capacity and do more training. We were then able to hire two more behavioral health staff to coordinate the MAT program, do individual therapy, and run the groups.” (Physician, DC)

“HRSA’s support for addiction treatment has allowed us to train more providers and better integrate MAT services throughout our organization.” (CEO, Maryland)

Looking Ahead

As the opioid epidemic continues to escalate, HCH programs will remain on the front lines of providing buprenorphine-based MAT to very vulnerable, high-need patients disproportionately impacted by this crisis. While some HCH programs have not yet begun programs or scaled them to meet community need, many HCH programs are providing significant levels of buprenorphine-based MAT and are rapidly growing the number of patients they are able to serve. These programs have overcome common challenges by adopting strategies that focus on increasing organizational support, facilitating staff training and collaboration, modifying the MAT program to ensure better access, and maximizing community partnerships and available resources. These strategies can be adopted by HCH programs and other health centers, and by other community providers looking for effective ways to expand access to treatment for the millions of people struggling with OUD.

This brief was prepared by Barbara DiPietro of the National Health Care for the Homeless (HCH) Council and Julia Zur and Jennifer Tolbert with the Kaiser Family Foundation. National HCH Council contractor time for work on this publication is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of an award totaling $1,625,741 with less than 1% financed with non-governmental sources. The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA, HHS, or the U.S. Government. For more information, please visit HRSA.gov.